The United States, a country that holds one of the highest incarceration rates in the world.

Continues to face intense scrutiny over aspects of its criminal justice system that many observers consider deeply troubling.

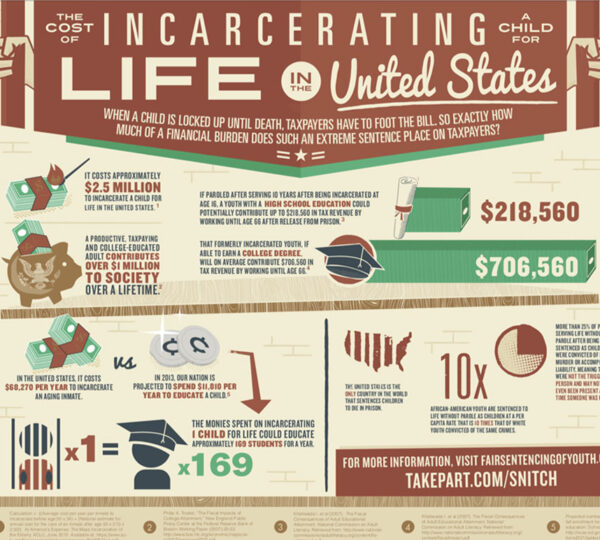

Among the most controversial realities is the sentencing of children to life imprisonment without the possibility of parole, a punishment that effectively condemns a person to spend the rest of their life behind bars, regardless of rehabilitation or personal growth.

According to long-standing research and reports published by organizations such as Human Rights Watch (HRW) and the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), at least 79 individuals who were younger than 14 years old at the time of their offenses have received life-without-parole sentences in the United States.

While legal reforms and court rulings in recent years have reduced the use of this punishment, the legacy of these sentences continues to raise serious ethical, legal, and humanitarian concerns.

A Sentence That Allows No Second Chance

Life without parole, often referred to as LWOP, is the harshest sentence available under U.S. law short of the death penalty.

For adults, it is controversial; for children, it has become a focal point of international criticism.

Under such sentences, individuals are denied any opportunity for release, regardless of evidence of maturity, remorse, rehabilitation, or changed circumstances.

Critics argue that imposing this punishment on children ignores decades of scientific research showing that children’s brains are still developing, particularly in areas related to impulse control, risk assessment, and decision-making.

The United States stands largely alone in this practice. International human rights treaties, including the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, prohibit life-without-parole sentences for minors.

Although the U.S. has signed but not ratified the convention, it remains one of the only countries in the world that has historically imposed such sentences on children.

Who Are the Children Affected?

The cases behind these statistics vary widely, but many share common patterns.

Some children were convicted of homicide committed during robberies or other violent crimes.

Others were sentenced under felony-murder laws, which allow individuals to be convicted of murder even if they did not personally kill anyone or use a weapon.

In several cases documented by advocacy organizations, children were prosecuted as adults for their alleged role in crimes committed alongside older peers.

Critics argue that this practice fails to adequately consider the power dynamics, fear, and immaturity that often influence children’s actions.

Research consistently shows that the vast majority of children sentenced to life without parole come from marginalized backgrounds.

Many grew up in environments marked by extreme poverty, unstable housing, exposure to violence, neglect, or abuse.

Structural racism has also played a significant role, with Black and Latino youth disproportionately represented among those receiving the harshest sentences.

The Case of Lionel Tate

One of the most widely cited cases in discussions of juvenile life sentences is that of Lionel Tate, who was arrested in Florida at the age of 12 for the death of a 6-year-old girl during what his defense described as a simulated wrestling match.

In 2001, Tate became one of the youngest individuals in modern U.S. history to receive a life-without-parole sentence.

The ruling drew national and international outrage, with critics arguing that a child lacked the capacity to fully understand the consequences of his actions or the legal process he faced.

Although Tate’s sentence was later reviewed and modified following legal appeals and public pressure, his case became a turning point in the broader debate over whether children should ever be tried and punished as adults.

It also highlighted how quickly a single case involving a minor can expose systemic flaws in the justice system.

Supreme Court Rulings and Legal Reforms

Over the past two decades, the U.S. Supreme Court has issued several landmark decisions limiting the harshest punishments for minors.

In Roper v. Simmons (2005), the Court ruled that the death penalty for crimes committed by minors was unconstitutional.

In Graham v. Florida (2010), the Court barred life-without-parole sentences for juveniles convicted of non-homicide offenses.

In Miller v. Alabama (2012), the Court ruled that mandatory life-without-parole sentences for juveniles, even in homicide cases, were unconstitutional.

Subsequent rulings required courts to consider youth, background, and potential for rehabilitation before imposing such sentences.

Despite these decisions, life without parole for juveniles has not been entirely abolished in the United States. Some individuals sentenced decades ago remain incarcerated under old rulings, while others have faced lengthy resentencing processes that do not guarantee release.

Moral and Psychological Concerns

Mental health experts and child development specialists overwhelmingly agree that children differ fundamentally from adults in their capacity for judgment and change.

Adolescents are more susceptible to peer pressure, more likely to act impulsively, and less capable of foreseeing long-term consequences.

Critics argue that sentencing a child to die in prison denies the possibility of redemption and contradicts the foundational principles of juvenile justice, which historically emphasized rehabilitation over punishment.

Supporters of reform also note that many incarcerated individuals who committed crimes as children have demonstrated significant personal growth, pursued education, and contributed positively within prison environments when given the opportunity.

An Ongoing National Debate

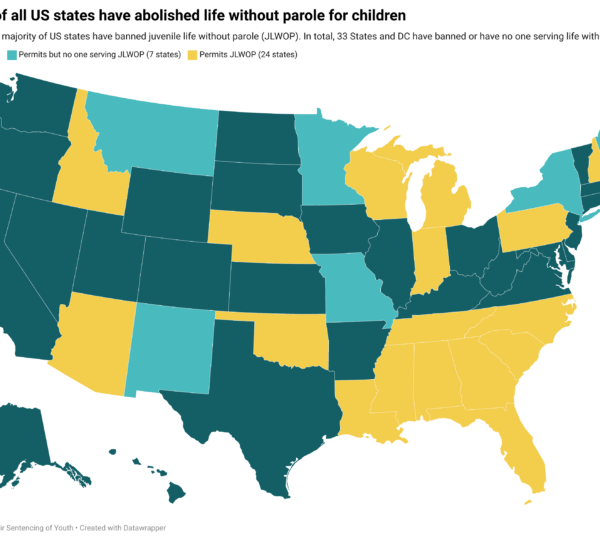

While some U.S. states have eliminated juvenile life-without-parole sentences entirely, others continue to allow them under limited circumstances.

Advocacy groups continue to push for nationwide reform, arguing that no child, regardless of the crime, should be permanently denied hope.

At the same time, families of victims emphasize the seriousness of violent crimes and the lifelong impact of loss.

The debate remains deeply emotional, balancing accountability with compassion and justice with mercy.

Conclusion

The reality that children as young as 12 or 13 have received life-without-parole sentences in the United States continues to challenge the nation’s understanding of justice, punishment, and human development.

While legal reforms have reduced the use of such sentences, their legacy remains a powerful reminder of how policy decisions affect the most vulnerable individuals in society.

As courts, lawmakers, and communities continue to reexamine juvenile sentencing laws, the question persists: Should a child ever be sentenced to a punishment that allows no second chance?

The answer will shape the future of juvenile justice in America for generations to come.

More Stories

Billie Eilish’s Brother Finneas Addresses Backlash After Her Grammys Speech

Cher Previously Discussed Having a Facelift – How She Looks Now at 79 and How AI Thinks She’d Look Naturally

I Baked Pies for Hospice Patients — Until One Day, One Was Delivered to Me and I Nearly Collapsed