The state of Missouri has set an execution date for a man convicted in the killing of a six-year-old girl whose disappearance in 2002 shocked a community and left a lasting mark on the region.

The Missouri Supreme Court ordered that Johnny Johnson be executed on August 1 at the state prison in Bonne Terre. Johnson was convicted in the death of Cassandra “Casey” Williamson, a kindergartner from St. Louis County.

Johnson has spent more than two decades on death row following his conviction for first-degree murder and related crimes. His case has moved through multiple levels of appeal before reaching this final stage.

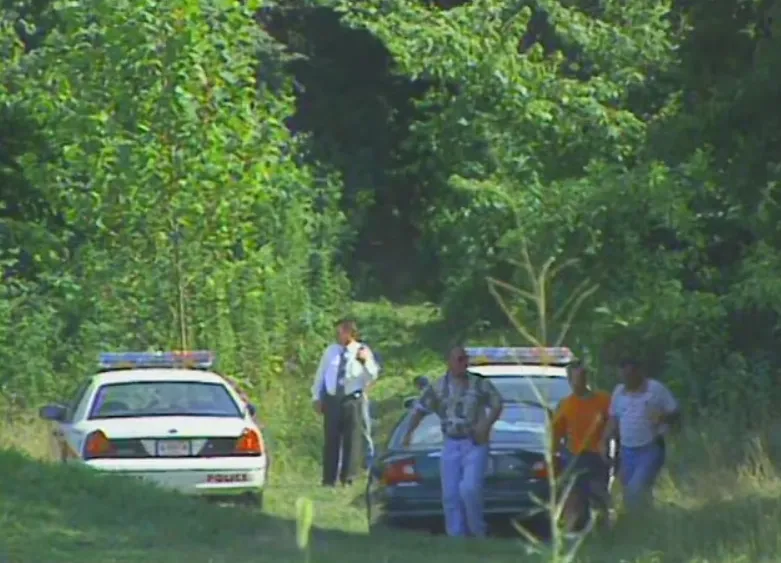

Casey Williamson was reported missing in July 2002 while staying with her family at a friend’s home in Valley Park, Missouri. The disappearance prompted an urgent search that drew in law enforcement and volunteers from across the area.

Family members reported that Casey had last been seen inside the home early that morning. When she could not be found shortly afterward, police were contacted and search efforts began immediately.

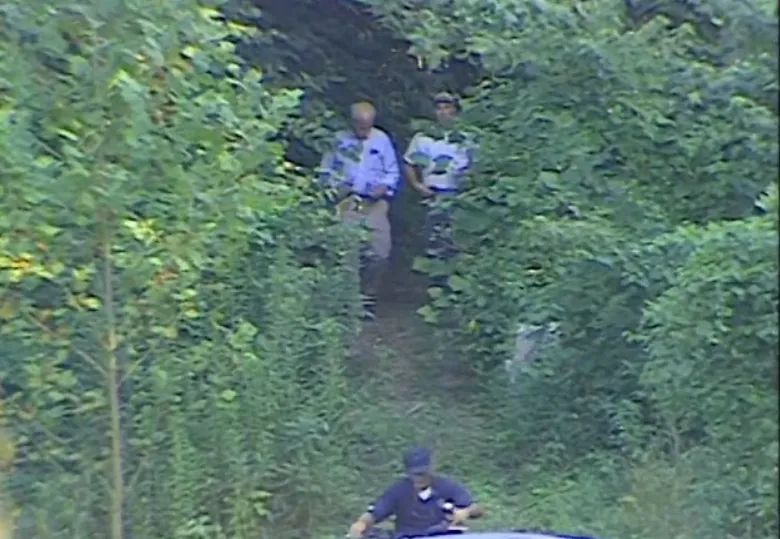

Dozens of volunteers joined officers from St. Louis County and federal agencies to comb nearby woods and areas along the Meramec River. The search continued for hours as concern for the child grew.

Later that day, Casey’s body was discovered less than a mile from where she was last seen. Investigators determined she had been taken to an abandoned industrial site nearby.

Johnny Johnson, who was 24 at the time, was staying at the home where Casey and her family were visiting. He was known to be a drifter and had a prior criminal history.

Witnesses reported seeing Johnson walking with the child earlier that morning. Police later apprehended him nearby as the investigation narrowed its focus.

Johnson eventually confessed to the crime and led investigators to the location where Casey’s body was found. Prosecutors said his statements and physical evidence supported the charges brought against him.

The child’s death was ruled a homicide caused by severe physical injury. Investigators concluded that the killing occurred during an attempted sexual assault.

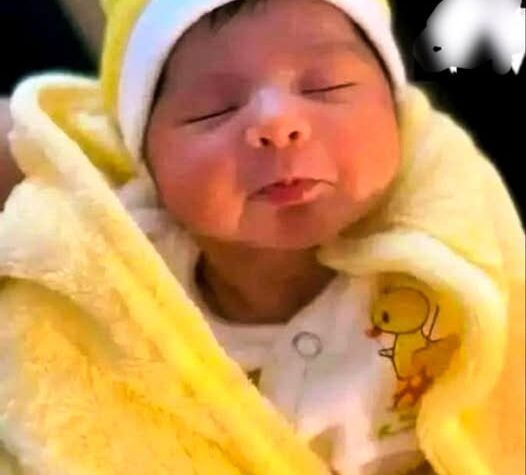

Casey was remembered by her family and teachers as a cheerful and energetic child. She loved riding her bicycle, singing, and spending time outdoors.

News of her death devastated the Valley Park community. Vigils were held, and residents expressed grief and anger over the loss of a young life.

In 2005, Johnson was convicted of first-degree murder, armed criminal action, kidnapping, and attempted forcible rape. He was sentenced to death for the murder charge and received additional life sentences for the remaining counts.

During the trial, Johnson’s defense team presented evidence of his long history of mental illness. Medical testimony indicated he had been diagnosed with serious psychiatric conditions beginning in his teenage years.

Defense attorneys argued that Johnson’s mental health impaired his judgment at the time of the crime. They asked jurors to consider a lesser charge, citing his psychiatric history.

Prosecutors rejected that argument, emphasizing the deliberate actions taken before and after the killing. They urged jurors to focus on the harm done to the child and her family.

The jury ultimately sided with the prosecution, returning a guilty verdict on all major counts. The death sentence was imposed following a separate penalty phase.

Since his conviction, Johnson has been housed at Potosi Correctional Center, Missouri’s primary death row facility. He has pursued multiple appeals and post-conviction challenges.

In 2012, Johnson sought to overturn his sentence, arguing that his mental illness should preclude execution. Courts denied the request, affirming the original verdict and sentence.

The setting of an execution date brings renewed attention to a case that has remained painful for Casey’s family. Relatives have previously said no sentence can undo their loss.

Advocates for victims say the decision marks the end of a long legal process. They note that the case has been reviewed repeatedly by courts over many years.

Opponents of capital punishment have raised concerns about executing individuals with severe mental illness. They argue such cases raise ethical and legal questions that deserve scrutiny.

Missouri officials have stated that executions proceed only after exhaustive judicial review. The state has carried out several executions in recent years following similar processes.

The August 1 execution is scheduled to take place at the Eastern Reception, Diagnostic and Correctional Center in Bonne Terre. The Department of Corrections has not released further procedural details.

Legal experts say last-minute appeals are common in death penalty cases. Courts will continue to review any filings submitted prior to the scheduled date.

For Casey Williamson’s family, the approaching execution revives memories of a loss that never truly fades. Friends say the family has focused on honoring Casey’s life rather than the circumstances of her death.

Community members who participated in the search in 2002 have also reflected on the case. Many recall the hope that accompanied the early hours of the search and the devastation that followed.

Law enforcement officials involved at the time described the case as one of the most difficult of their careers. They noted the scale of the response and the emotional toll on everyone involved.

The case has been cited in discussions about child safety and the risks posed by unfamiliar adults in domestic settings. Advocates emphasize vigilance and community awareness.

As the execution date approaches, Missouri officials have reiterated that the legal process has run its course. The courts have upheld the conviction and sentence at every stage.

The story of Cassandra “Casey” Williamson remains one of profound loss. Her name continues to be remembered in Valley Park as a reminder of a child whose life ended far too soon.

While the justice system moves toward its final step, the impact of the crime extends far beyond the courtroom. It lives on in the memories of a family and a community forever changed.

Casey would be an adult today. Instead, she is remembered as a six-year-old girl with a bright smile and a joyful spirit.

As Missouri prepares to carry out the sentence, the case underscores the enduring consequences of violent crime. It also highlights the long and complex path that capital cases take through the American justice system.

For many, the hope is that remembering Casey’s life, rather than focusing solely on the punishment, honors her in the most meaningful way.

More Stories

Following Epstein-Related Documents, Melinda Gates Addresses Allegations Involving Bill Gates

The daughter of the famous singer has just passed away…see more…

Questions Grow After Fatal Police Encounter Claims Life of 3-Year-Old Kentre Baker